We were told Electronic Logging Devices (ELDs) would improve safety and compliance. That they’d protect drivers and the public.

But that’s not what’s happening.

Instead, ELDs have become a wide-open backdoor into the commercial vehicle and, by extension, our national infrastructure. What was supposed to prevent abuse is now enabling it, through software that’s exploitable, unaudited, and often controlled by companies you’ve never heard of.

What started as a safety initiative has evolved into something far more complicated. And far more vulnerable.

Important note: Before we proceed, it's worth noting that there are reputable ELD providers available. Companies that follow the rules, respect data privacy, and genuinely care about safety and compliance. This article is not about them.

This is about the rest. The ones exploiting loopholes, hiding behind white-label names, and turning federally mandated devices into surveillance tools, log-manipulation engines, and cybersecurity liabilities.

Brief History of the ELD

The push for electronic logging started decades before the 2017 mandate. In 1986, the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) challenged the Department of Transportation (DOT), lobbying for the mandatory use of electronic logs in all commercial trucks. What followed was a two-year standoff.

By 1988, the two sides reached a compromise. Instead of full-blown ELDs, trucks were required to use Automatic On-Board Recording Devices (AOBRDs). These captured basic driving data but were far less intrusive than modern ELDs, satisfying both safety advocates and the trucking industry. Once in place, the push for stricter logging technology was shelved for over a decade.

In 2000, the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) took up the fight again with one goal: to reform the broken Hours of Service (HOS) system, believing that this would fix all the safety issues. FMCSA saw ELDs as the solution, but in 2004, the attempt failed.

It wouldn’t fail a second time.

In 2010, Congress stepped in. On July 6, 2012, lawmakers passed MAP-21 (Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century), which directed the FMCSA to mandate the use of ELDs. The final rule was published on December 16, 2015, with a three-year compliance window.

By December 18, 2017, the mandate kicked in. Paper logs were out. From that point on, only ELDs, or grandfathered AOBRDs, could be used to record driver hours.

What Is an ELD?

An Electronic Logging Device (ELD) is a piece of hardware that plugs into a commercial truck’s engine and automatically records when the engine is on, when the truck is in motion, and the distance traveled. Its core purpose is to enforce HOS rules and stop drivers from falsifying logs or working dangerously long hours.

But it’s not just a plug-and-play device. Most ELD systems include:

A tracking unit is installed in the truck,

A mobile app used by the driver,

Cloud-based fleet software is used by dispatchers or management.

Together, they report the driver’s status in real-time and are marketed as tools to support compliance, safety, and operational planning.

That’s the theory, anyway…

Self-Certification of ELDs

If people can get away with doing illegal things, they will. And this is where it gets messy.

You might assume that something as critical as an electronic logging device, one that controls how long someone can legally operate an 80,000-pound vehicle, would be rigorously tested and approved by the federal government.

It’s not.

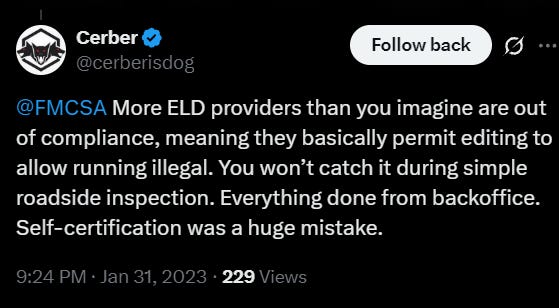

The FMCSA doesn’t test ELDs. It doesn’t verify what they do or how they do it. Instead, it runs a self-certification system. If a company says its device meets the technical specs, it submits a form, uploads a sample output file, and adds itself to the list of “approved” ELD providers. That’s it.

No independent review. No cybersecurity evaluation. No real barrier to entry.

Once on the list, these companies are free to market their products as FMCSA-certified, creating a false sense of security for carriers, shippers, and enforcement officers alike.

If this concerns you, please continue reading.

White-labeled ELDs

It is far more concerning than one may imagine.

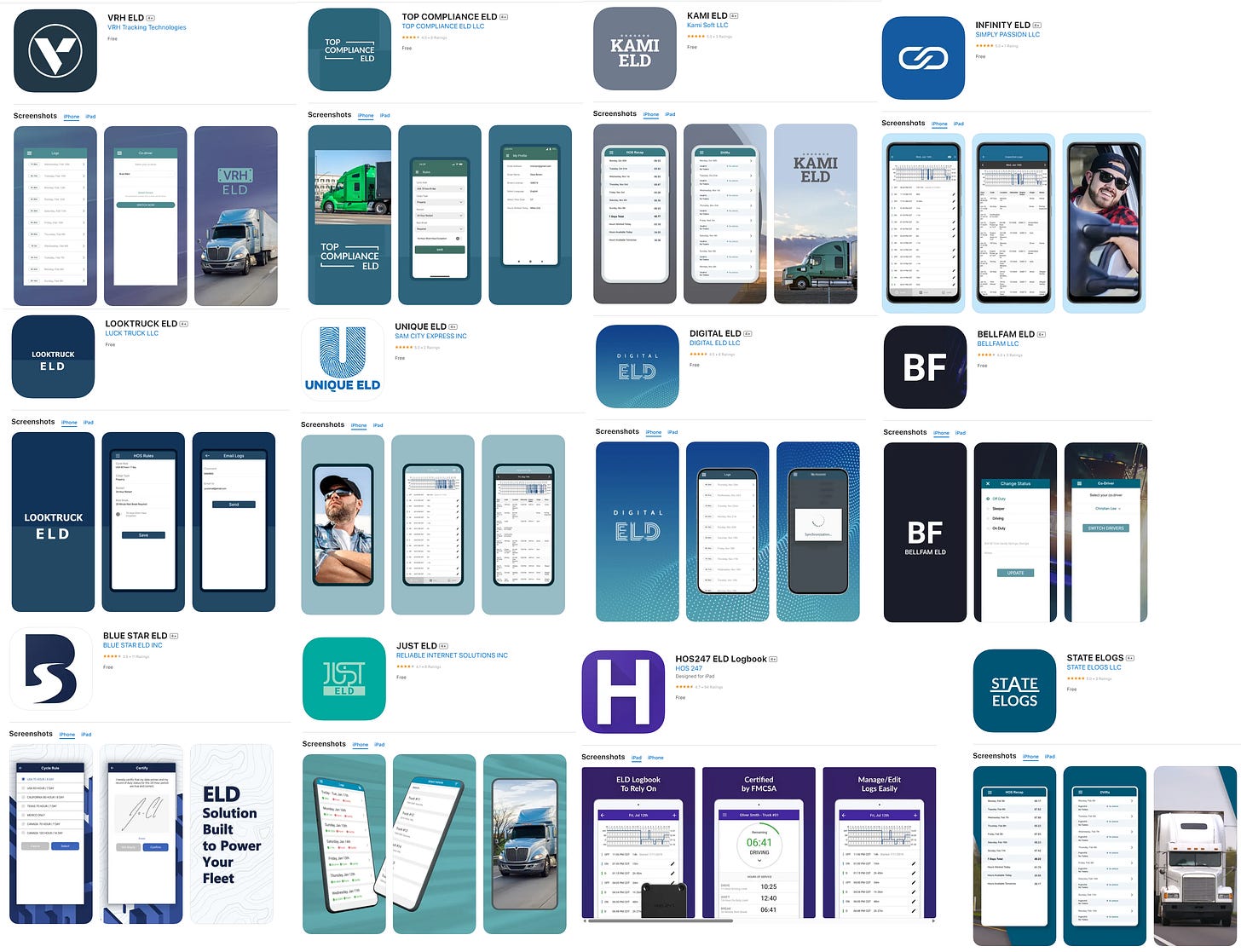

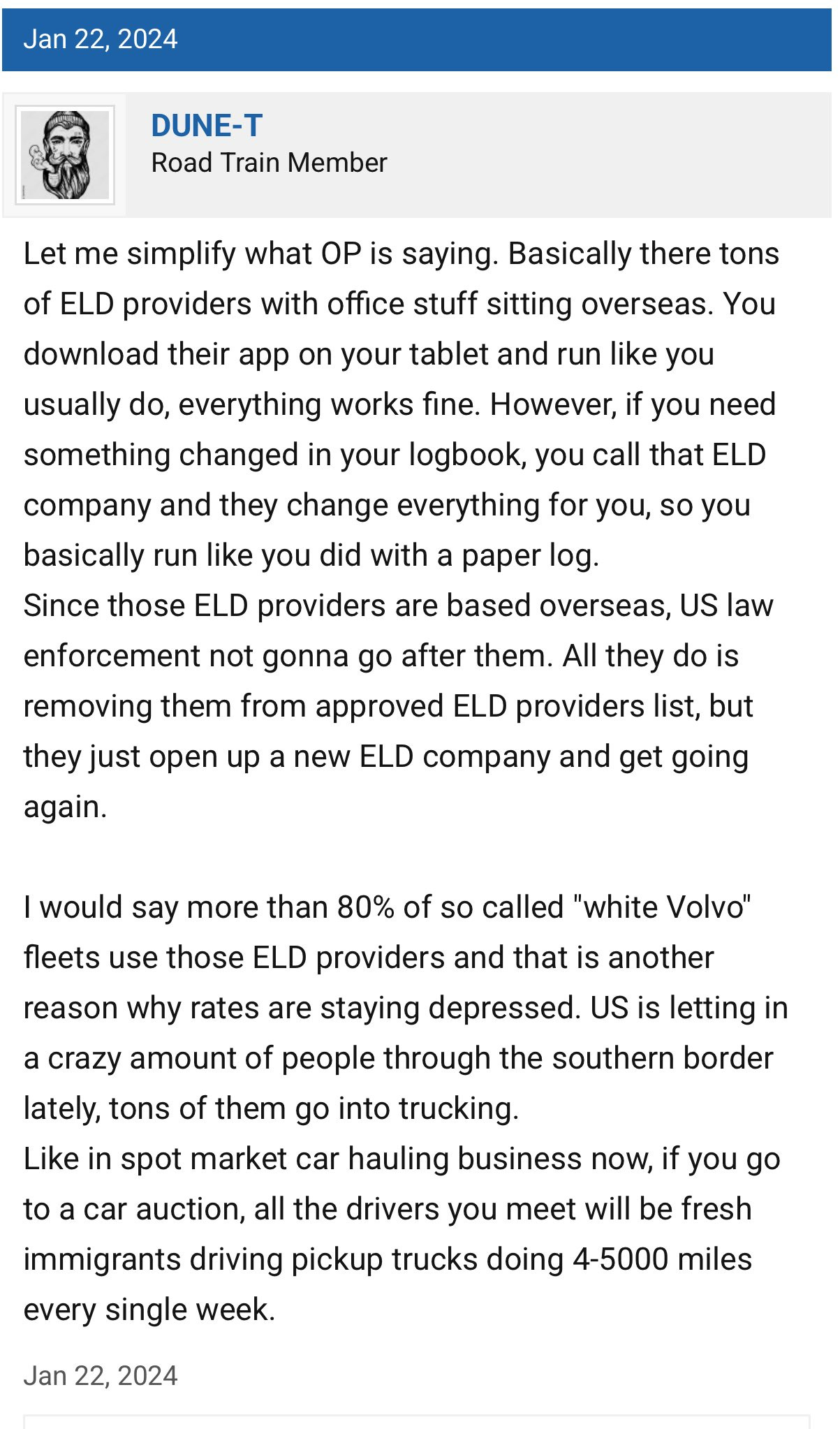

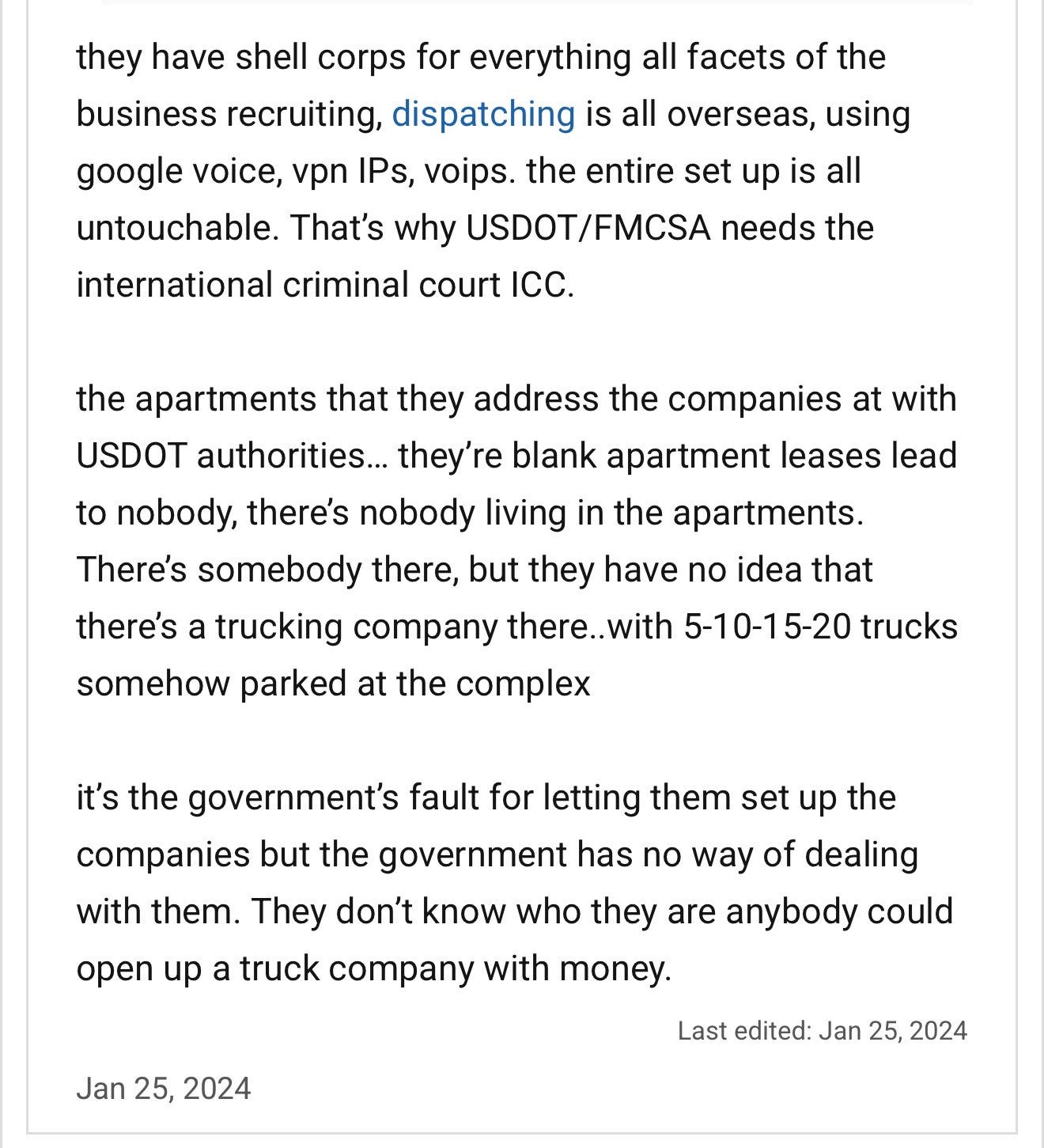

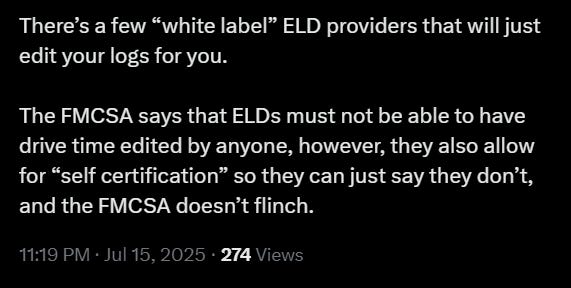

Of the 900+ ELDs on the FMCSA’s approved list, many aren’t even real products in the traditional sense. They’re white-labeled clones. The same core software, often developed overseas, is repackaged under different names with new logos and splash screens.

It’s like slapping a different sticker on the same car and pretending it’s a new model. Or, if you’re in the industry, it’s eerily similar to the chameleon carrier game.

This makes it nearly impossible to know who is actually behind a device or what kind of access they have. Many of these clones share the same codebase, the same vulnerabilities, and sometimes even the same backend servers. So, when one gets pulled from the FMCSA list for non-compliance? It often reappears under a new name.

If this sounds like an enforcement nightmare, that’s precisely because it is.

I’ve reviewed dozens of so-called "certified" ELD providers. Most are foreign-owned or operated outside the U.S., and virtually none undergo meaningful cybersecurity oversight. That means foreign entities could be sitting on a goldmine of real-time freight intel — driver locations, border crossings, cargo movements, delivery schedules, shipping documents, and more.

And these devices don’t just log hours. Some of them track everything.

Many ELD apps request, or quietly gain, full access to a driver’s phone: contacts, camera, microphone, files, text messages, location history. There’s absolutely no operational reason for that unless you’re in the business of surveillance or shady data harvesting.

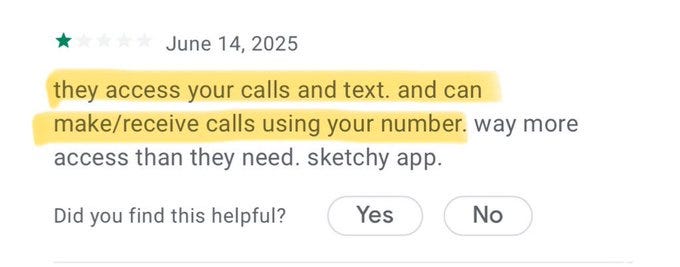

In one user review, a driver reported that the ELD company made phone calls on her behalf. Others have noted unauthorized access to messages and photos.

This isn’t just creepy. It’s a security risk. For the driver. For the freight. For the country.

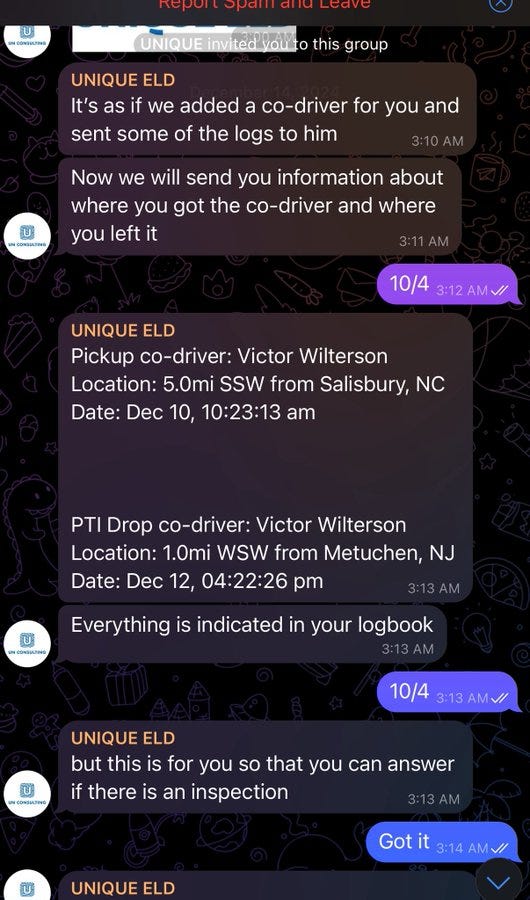

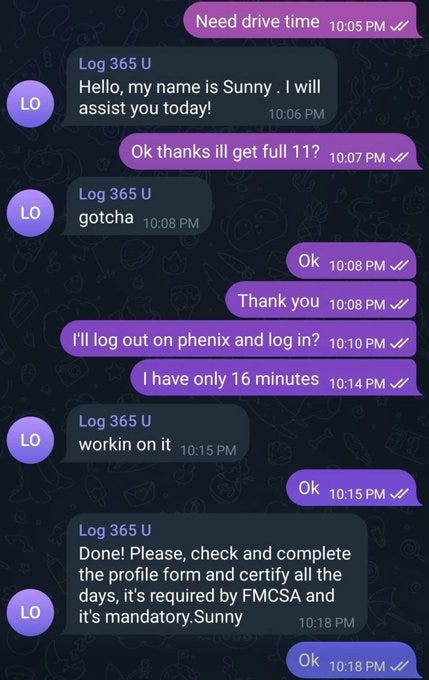

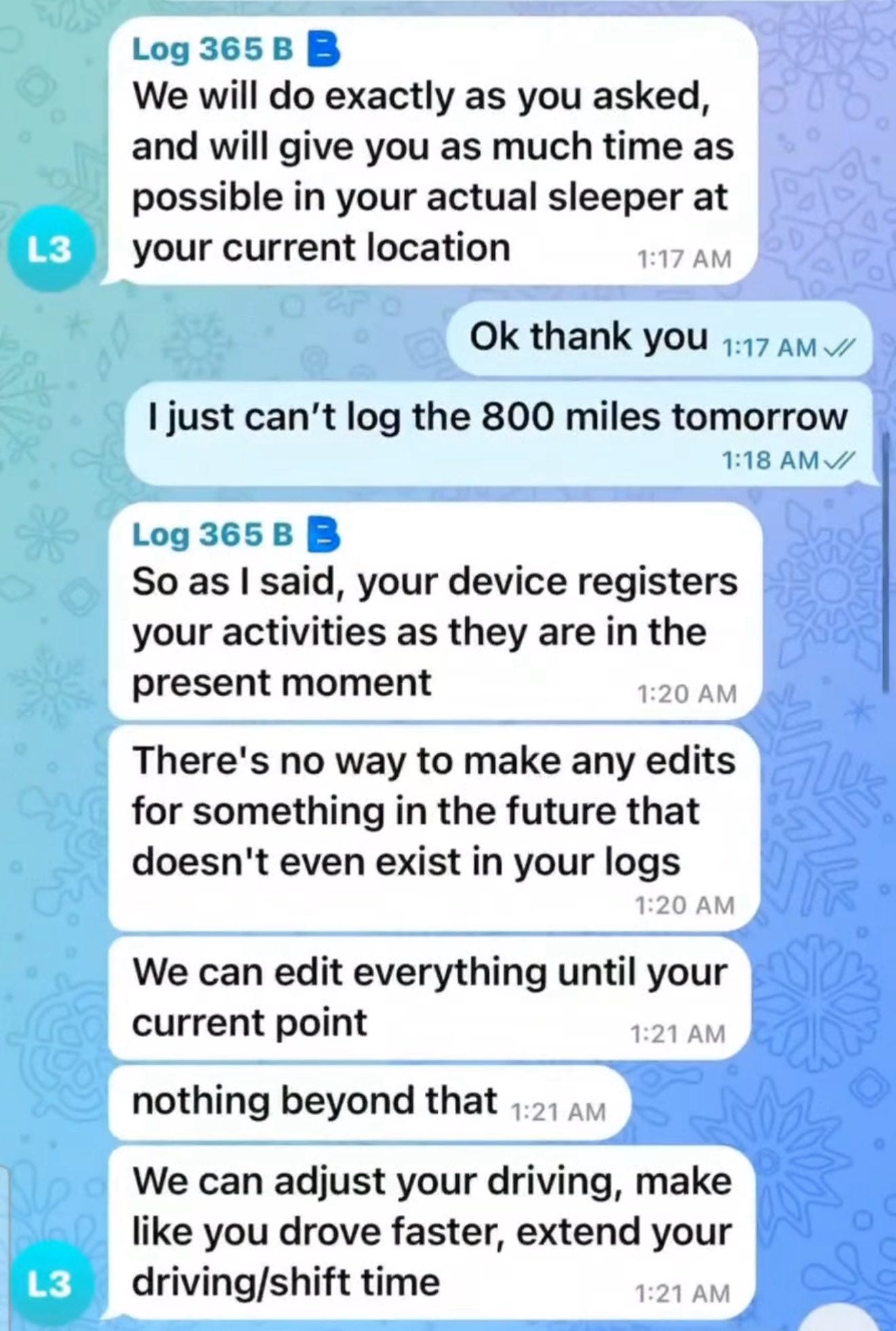

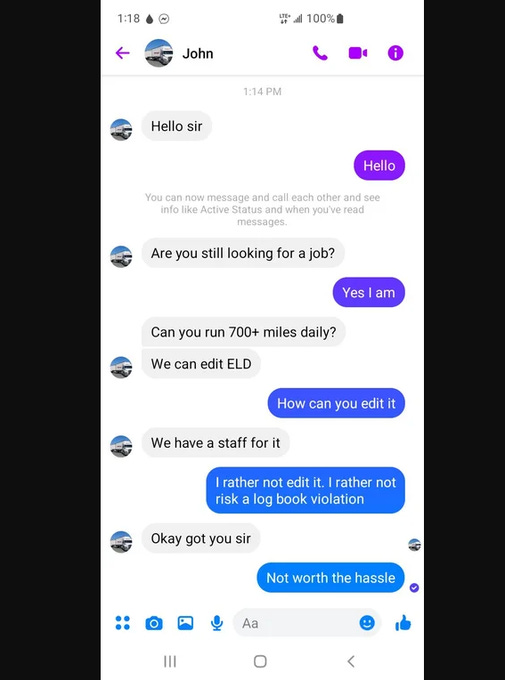

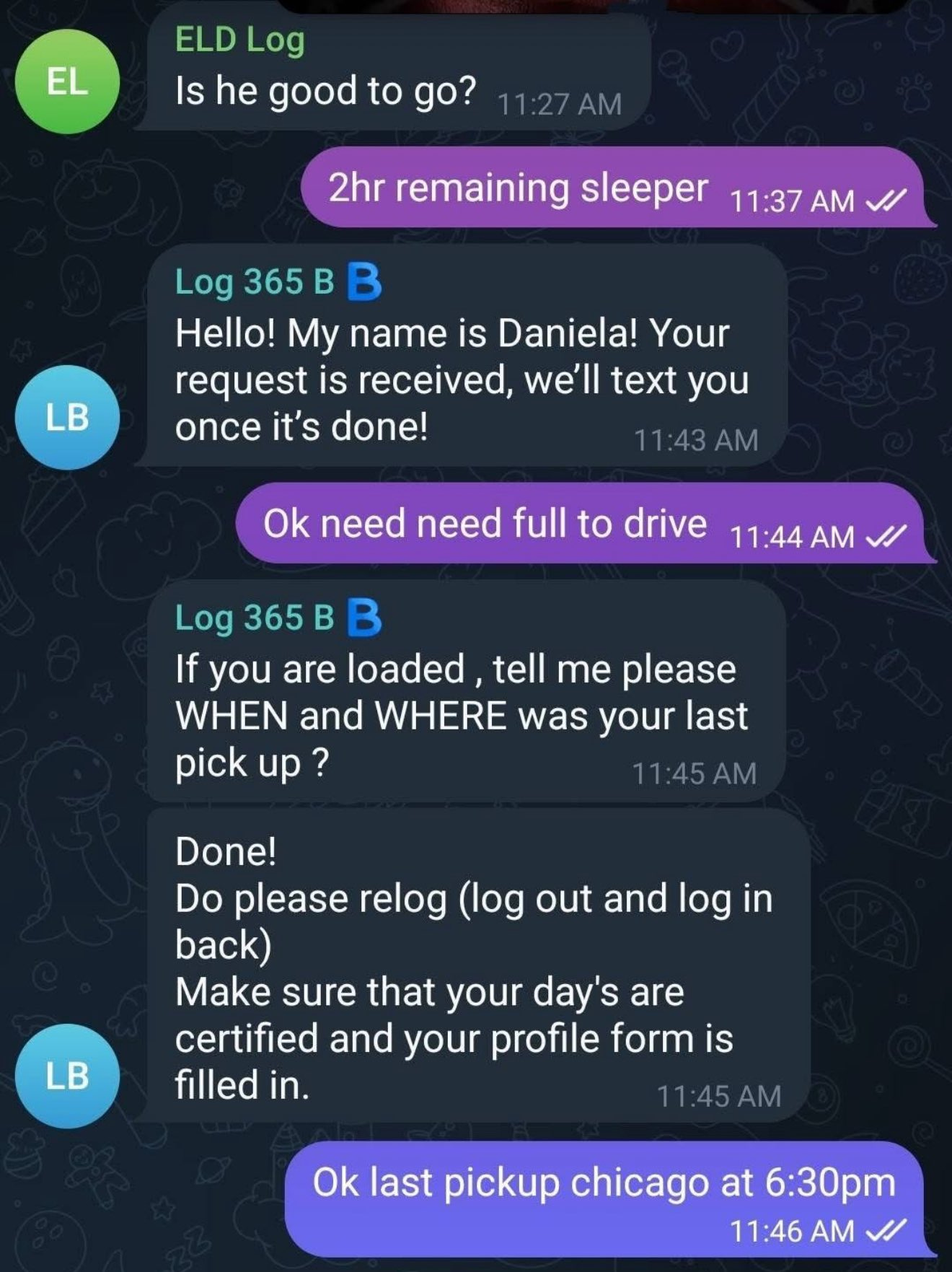

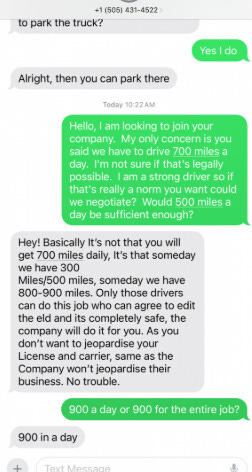

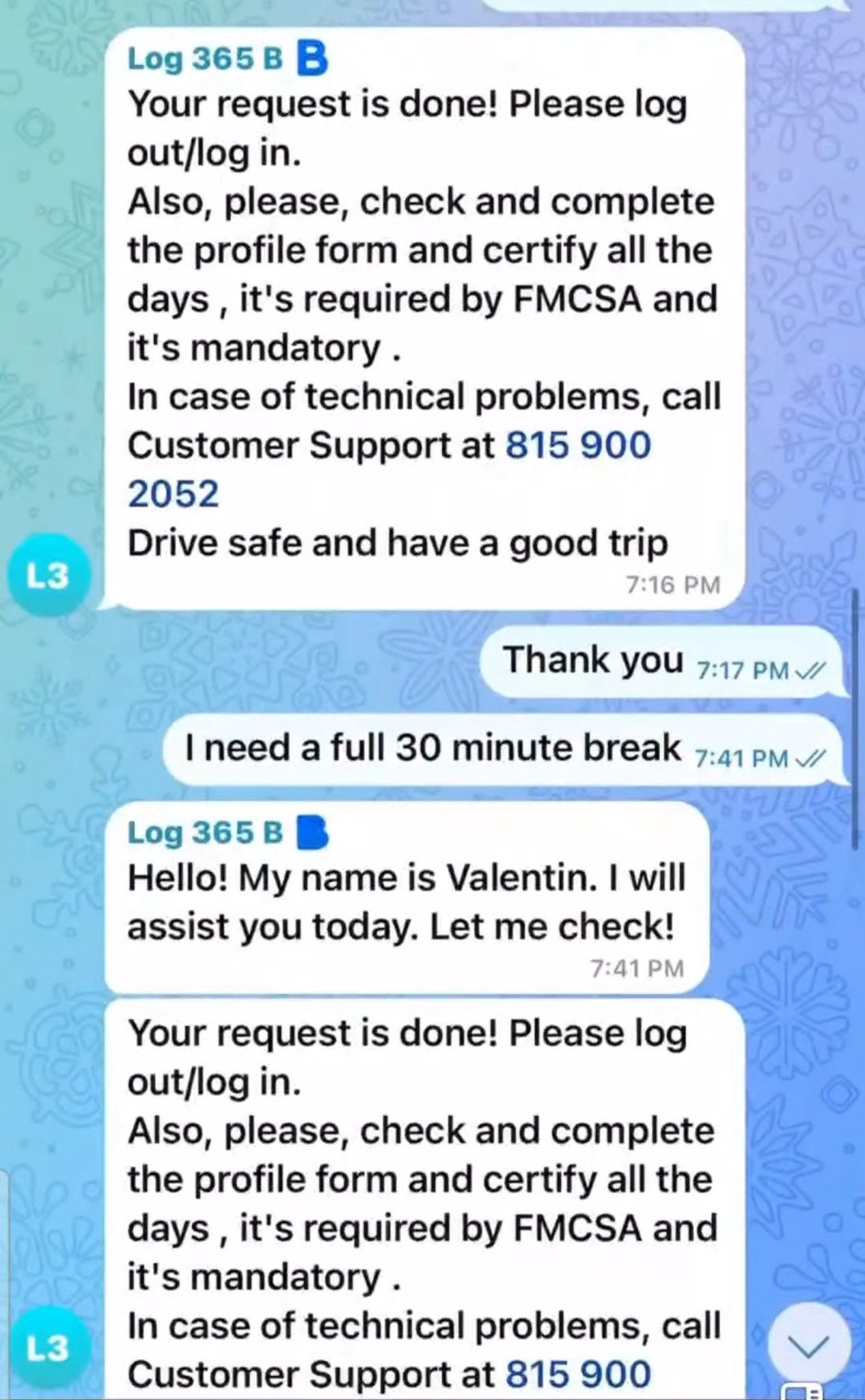

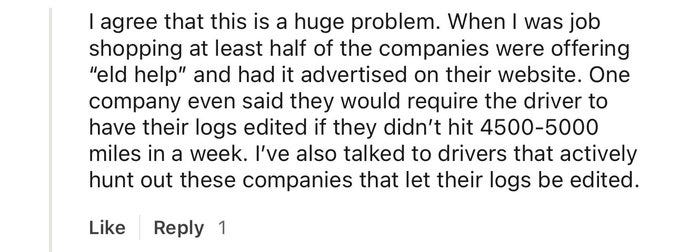

With backend access, tech teams can “reset” or alter logs on demand. That gives dispatchers the power to override reality, pushing drivers past legal limits while maintaining a perfectly clean digital paper trail.

It’s coercion disguised as compliance. And it’s incredibly dangerous.

Open your app store and search “ELD.” You’ll see hundreds of apps with almost identical interfaces.

What was sold as a safety solution has devolved into a fractured, opaque ecosystem of exploitable software.

It’s not just bad policy.

It’s a backdoor into critical infrastructure.

No change in driver or public safety.

Take the company behind a deadly wreck in Texas, where a driver fell asleep and killed 5 people. The driver’s particular trip required a team (2 drivers). But there’s no evidence, to this day, that a co-driver was present.

How did this happen?

Given the circumstances, it's reasonable to conclude that a 'ghost driver' was entered through the ELD system, allowing someone to falsify logs or bypass HOS limits without immediate detection.

This isn’t just a logbook issue. This is an ELD accountability issue. We don’t know which ELD was used, whether logs were tampered with, or whether the device even captured accurate data to begin with. And because the inspection system doesn’t require enforcement officers to record the ELD used, we’ve lost a critical opportunity to trace failures back to the software that enabled them.

This is precisely what happens when we treat self-certification as a substitute for enforcement.

And yes, “tech teams” really reset hours.

No doubt this correlates with the increase in freight and identity theft.

A dispatcher sends shipment details, including pickup location, delivery address, and cargo contents, directly to the driver’s ELD.

That data flows through the ELD’s backend, often to servers run by third-party tech firms, many of which are overseas or operate without proper oversight.

Not long after, a specific truck carrying $1 million worth of Nintendo Switch consoles is hit in a targeted cargo theft.

Sure, it could have been someone watching the warehouse. Maybe a tip-off. Maybe pure luck.

But let’s not kid ourselves. When shipment details, GPS data, and driver communications are flowing through third-party tech platforms, many of which are hosted overseas, it would be naive to assume those data centers are operating with airtight security and zero unauthorized access.

We’re not talking about hypothetical vulnerabilities. We’re talking about a live feed of supply chain movements flowing through unvetted software that no federal agency has ever meaningfully audited.

And all of this is happening under the guise of “compliance.” It’s a data breach by design.

When ELD apps are granted full access to shipment details, GPS tracking, driver messages, and shipping documents, they become a goldmine for anyone watching the backend. Combine that with lax cybersecurity, foreign ownership, or bad actors inside the tech firm, and someone has a live feed of what’s moving where and when.

Reminder, everything is transported on a truck at some point. This isn’t just about game consoles. It’s about pharmaceuticals. Ammunition. Military parts. Critical infrastructure components.

And we’ve handed over that visibility, without vetting who’s holding the keys.

The FBI Warned Us

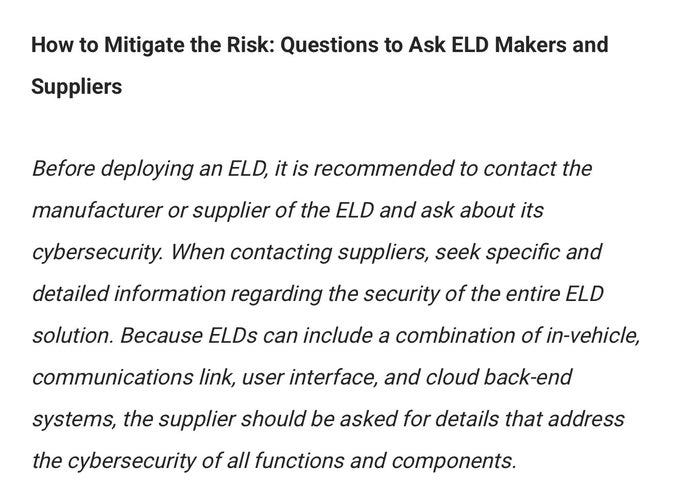

In February 2020, the FBI issued a formal warning about the cybersecurity risks posed by Electronic Logging Devices.

In their report, the Bureau made it clear: ELDs are a target. Cybercriminals can exploit vulnerabilities to move laterally into a company’s larger network, gaining access to sensitive data like:

Driver information

Business and financial records

Real-time vehicle tracking

Customer lists and cargo manifests

With that access, attackers could install malware or ransomware, rendering vehicles, dispatch systems, or entire fleets inoperable until the ransom is paid. The FBI even outlined potential red flags, such as unusual network traffic or unauthorized file sharing, and urged companies to monitor these risks closely.

But here’s the kicker:

“Specifically, the FBI points to insufficient vetting and testing of ELDs as a major cause for concern. The Bureau’s Cyber Division notes that the FMCSA relies heavily on the ELD self-certification process.”

— FBI issues warning about ELDs, CDLLife

Let that sink in: The FBI is warning us about the exact same self-certification loopholes that still exist today.

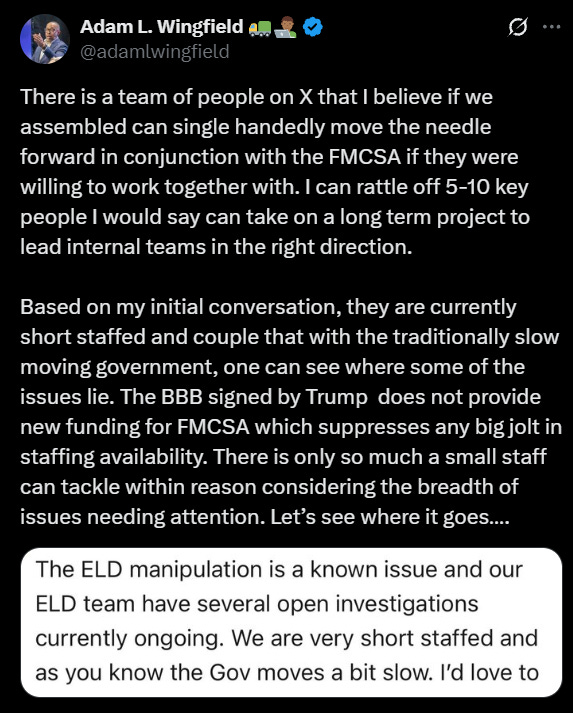

And what has FMCSA done since that warning? I don’t know.

But I do know self-certification continues.

No mandatory vetting. No formal testing process before an ELD hits the road.

So while we debate whether a driver was a few minutes over their HOS limit, foreign-owned software with backend access to supply chain intel is skating past enforcement entirely. And we’ve been told, by the FBI themselves, that we’re leaving the door wide open.

What Needs to Be Done… Like Yesterday

Record the ELD used during every HOS violation.

If a driver is cited for falsifying logs or violating Hours of Service rules, the enforcement officer must document the specific ELD used. This simple action would expose patterns of abuse, flag non-compliant devices, and help clean up the FMCSA’s bloated and broken list of “certified” providers.

With ELD data tied to inspection records, it becomes easy to identify the software fueling non-compliance. These apps, and their clones, should be permanently removed from the approved list. No rebranding, no backdoor re-entries. Just gone.

Create a real certification process.

Self-certification has failed. The FMCSA must implement an actual review process that verifies an ELD’s functionality, security, and data access permissions. If a device tracks more than what’s necessary to log hours, like phone contacts, messages, or photos, it doesn’t belong on the road.

This isn’t just an administrative problem; it’s a safety crisis with national implications. We don’t need more devices. We need accountability.

We say we want to solve freight fraud. But so far, we’re still spinning our wheels and chasing problems downstream that can’t be fixed without going upstream.

To be clear, none of this will stop low-quality carriers or drivers from entering the industry. However, it will help flag those who shouldn’t be operating or hiring unqualified drivers in the first place.