Highway Safety vs. Modern Sensitivities: The English Language Proficiency Rule

In the name of diversity, equity, and inclusion, unsafe carriers are just misunderstood...

This article is not about immigration, politics, or who “belongs” in trucking. It’s about why English Language Proficiency has been a federal safety requirement for commercial drivers for decades. This is not some new rule Trump pulled out of his head just because he can.

Much of the public commentary surrounding the English Language Proficiency (ELP) enforcement fundamentally misunderstands what is actually happening. So, before we even start, it is important to clarify what an out-of-service (OOS) violation is. And what it is not.

When a driver is placed out of service, he does not lose his commercial driver’s license (CDL), and he is not permanently removed from the road. An OOS is not a trucking ban. It is a temporary safety hold. Basically, a time-out.

The driver is required to stop operating the truck until the specific violation is corrected. Once that condition is “resolved,” the driver may legally return to service and continue driving. And sometimes this means just after the enforcement officer drives away.

Here, Axios, let me help you.

This Requirement Is Older Than the Debate Around It

Truck drivers have been required to read and speak English since 1937.

The English Language Proficiency requirement appears today in the Code of Federal Regulations at 49 CFR § 391.11(b)(2) and has been codified as part of federal driver qualification standards since at least 1970. Its underlying safety rationale dates back even further, to the earliest federal motor carrier safety rules adopted in 1937.

Despite recent headlines, this is not a modern policy initiative and is not tied to any contemporary administration. It is a longstanding federal safety standard that has existed across multiple generations of trucking, enforcement agencies, and political leadership.

49 CFR § 391.11(b)(2) — General qualifications of drivers states:

“A person is qualified to drive a commercial motor vehicle if that person—

(2) Can read and speak the English language sufficiently to converse with the general public, to understand highway traffic signs and signals in the English language, to respond to official inquiries, and to make entries on reports and records.”

To be very clear. This rule predates Donald J. Trump.

It also predates FreightX.

And it predates most people currently arguing about it.

Timeline: English Language Proficiency in U.S. Trucking

1937

Federal motor carrier safety regulations establish the foundation for driver qualification standards, including the expectation that drivers can communicate sufficiently for safety-related purposes.

1970-ish

Formal codification. The English language proficiency requirement is codified in the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Regulations. 49 CFR § 391.11(b)(2).

2004-2005

The Commercial Vehicle Safety Alliance (CVSA) votes to add ELP violations to the North American Standard Out-of-Service (OOS) Criteria, effective April 1, 2005, recognizing that an inability to communicate with inspectors poses an immediate safety risk.

Despite this, FMCSA enforcement personnel are initially instructed to cite ELP violations but not place drivers out of service.

2007

On July 20, 2007, a memorandum reversed that approach, directing inspectors that if a driver cannot understand and respond to official inquiries and directions in English, the driver must be placed out of service in accordance with CVSA criteria

2016

The Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) issued internal enforcement guidance that removed the requirement to place drivers out of service for failing to meet the English language proficiency standard. Under that policy, drivers could be cited but not immediately taken off the road solely for ELP violations.

***The timing here is quite ironic, as it barely predates the mass surge of immigrants into the United States. And into the trucking industry.

May 20, 2025

The FMCSA issued updated enforcement guidance rescinding the 2016 memo and restoring inspectors’ authority to place drivers out of service for ELP violations.

June 25, 2025

The Commercial Vehicle Safety Alliance (CVSA) incorporated ELP noncompliance into the North American Standard Out-of-Service Criteria, meaning drivers who fail the English proficiency assessment can be placed out of service during roadside inspections.

Post-June 2025

Public messaging chaos ensues. The English Language Proficiency rule seems to be the only safety standard routinely reframed as discrimination, despite being older than nearly every modern trucking regulation.

FYI, this enforcement is not ICE. Drivers are not automatically deported for failing an ELP assessment. An out-of-service order does not revoke a CDL, and it does not permanently remove someone from the workforce.

If I had $5 for every headline or X post that needed correcting, I would be rich, rich.

Compliance or Control? Or Safety?

The narrative that the ELP enforcement is about control or exclusion collapses under the lightest scrutiny. As of this morning, 10,188 English Language Proficiency out-of-service violations have been issued between June 25, 2025, and December 12, 2025.

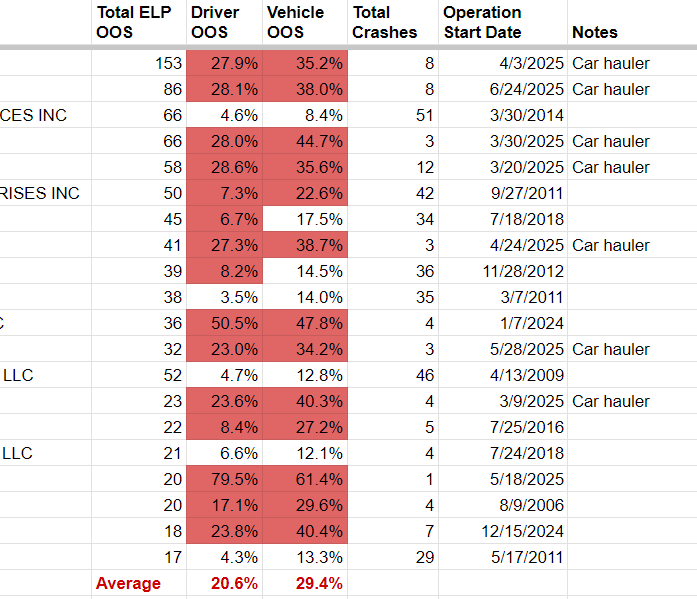

To understand what sits behind that number, I analyzed the top 20 carriers associated with these violations, reviewing their driver out-of-service rates, vehicle out-of-service rates, total crash counts, and operating start dates to assess how long each operation has been active.

My findings:

Driver and vehicle out-of-service rates among these carriers are well above national averages.

Many of the highest ELP violators are newly formed carriers, some of which have been operating (or operated) for only a few months.

Several of the car haulers are actually the same underlying operation. They repeatedly get shut down and resurface under new company names and USDOT authorities.

Crash counts are not trivial, even for companies with very short operating histories.

High ELP out-of-service counts do not exist in isolation here. They directly correlate with poor vehicle maintenance, unsafe driving practices, elevated crash involvement, and short-lived operating authorities.

Let me be very, very clear. This is NOT what well-run American trucking companies look like. And it should concern anyone who shares the road with an 80,000-pound vehicle (which is everyone).

A safety rule is not “unfair” simply because it is uncomfortable to enforce.

It becomes dangerous when it is ignored.

Ahem. California.

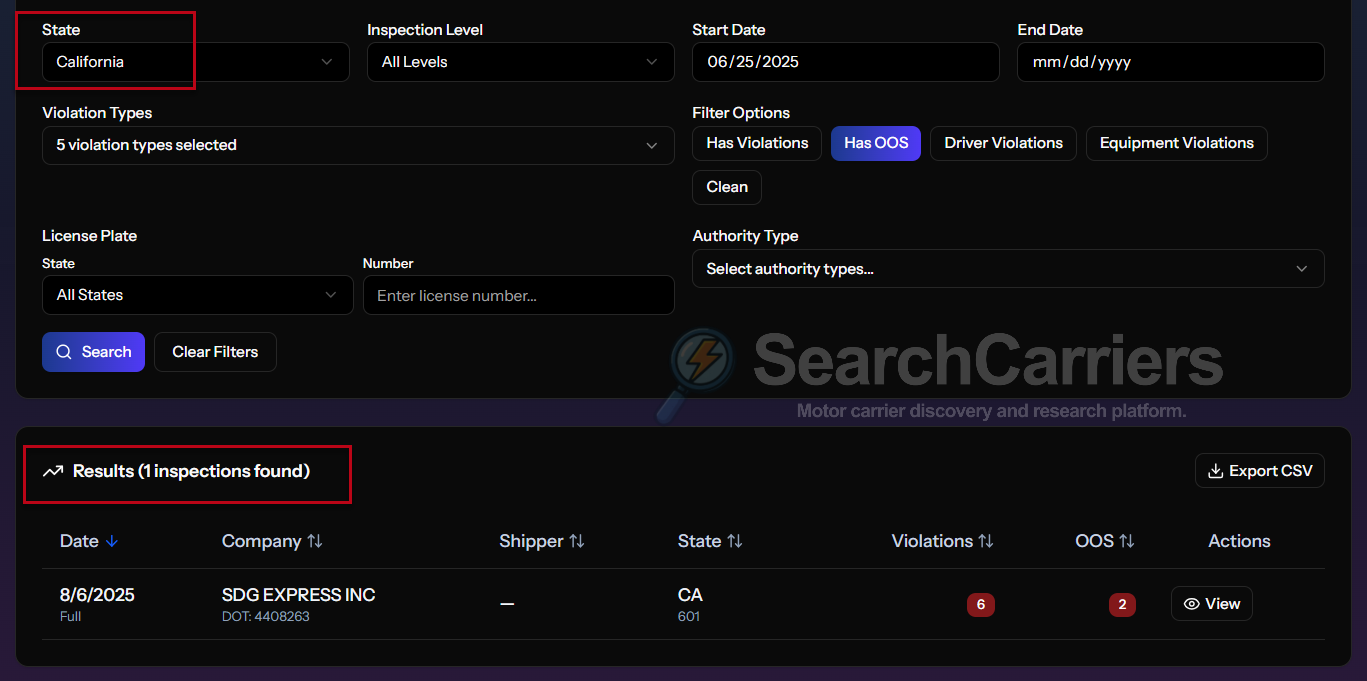

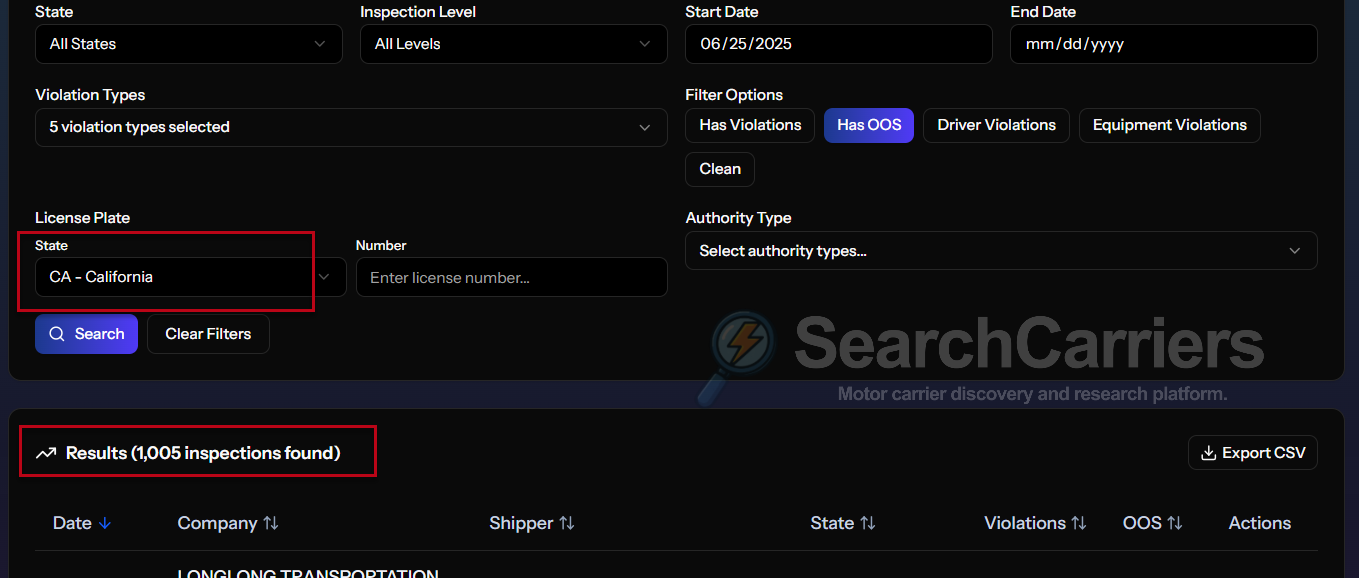

Since June 25, 2025, California has issued no more than ONE English Language Proficiency out-of-service violation.

At the same time, 1,005 trucks domiciled in California have been placed out of service for ELP violations in other states.

California isn’t producing safer drivers. It’s producing drivers who are being caught elsewhere. California truck drivers are not restricted to the state of California. Unfortunately, their refusal to enforce the ELP pushes the risk onto the rest of the country.

This is not up for debate.

It’s easy to attempt to debate English Language Proficiency in the abstract, as policy, enforcement, or politics. It is much harder to do so when confronted with what actually happens on the side of the road when things go terribly wrong.

When crashes happen, language is no longer a technical requirement. It becomes the difference between minutes and hours. Between survival and silence.

Here are two examples. Please know there are many, many more.

October 5, 2025

After a semi-truck slammed into their car, killing his 21-year-old brother, Toby, just 16 years old, ran to the truck driver and begged him to call 911.

The driver couldn’t understand him.

According to Toby, the truck driver barely spoke English. Instead of calling for help, the driver handed Toby his phone, forcing a teenager who had just witnessed his brother’s death to communicate with 911 dispatchers himself.

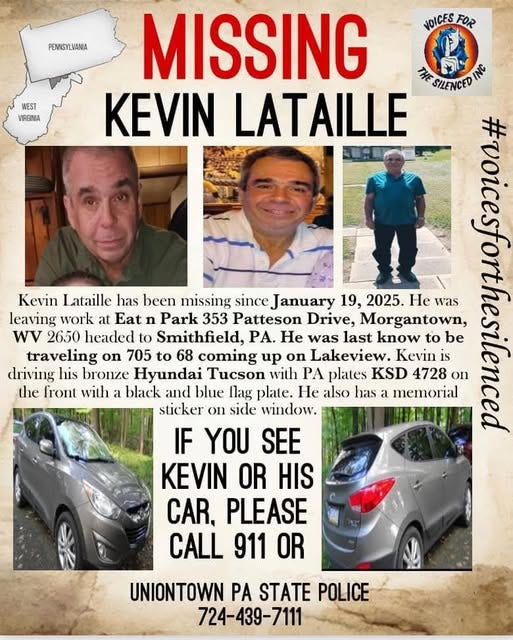

January 19, 2025

Kevin Lataille was 59 years old. A U.S. Navy veteran. He had just finished his shift at the Eat’n Park and was heading home during a snowstorm. Before leaving, he called his wife, Lisa.

“Hey, I’m leaving,” he told her. “I’ll be careful.”

He never made it home. She reported him missing.

Earlier that day, truck driver Sukhjinder Singh, 37, jackknifed his truck on the Cheat Lake Bridge in West Virginia. During the incident, Singh ran Lataille’s vehicle off the bridge and into the freezing river below.

A week later, rescue crews recovered Kevin and his vehicle from the icy water.

According to court documents, Singh did not call 911. He did not attempt to call 911. Singh does not speak English. He was unable to communicate with tow truck operators or law enforcement without a translator.

—

I do not share these stories for “shock value.” I share them because they illustrate the exact scenarios federal safety regulations are designed to address. Or supposed to address.

After a crash, a commercial truck driver must be able to call 911, explain what happened, follow dispatcher instructions, communicate with law enforcement, and help coordinate the emergency response. When that cannot happen, the consequences are measured in lost time, lost evidence, and lost lives.

This is why English Language Proficiency exists as a safety requirement.

This was never supposed to be a topic of political or immigration debate. It became one because enforcement made people “uncomfortable.”

English Language Proficiency has been a federal safety requirement for nearly a century. The law did not change. The risk did not change. What changed was whether we were willing to enforce a rule designed to protect the public.

The data shows that English Language Proficiency violations are not occurring in isolation. They cluster with elevated driver out-of-service rates, poor vehicle maintenance, higher crash involvement, and short-lived operating authorities.

Out-of-service enforcement does not end careers.

It does not revoke licenses.

It does not deport drivers.

English Language Proficiency is not about exclusion.

It is about safety and accountability.

And accountability is the bare minimum the public should expect from anyone entrusted with an 80,000-pound vehicle on America’s roads.

When the next crash happens and minutes turn into hours because no one can call for help, please remember: This was never supposed to be about feelings, politics, or inclusion. It’s about holding everyone who operates an 80,000-pound missile on America’s highways to the same basic standard that’s been on the books since 1937.

Anything less isn’t compassion. It’s blantant negligence.

On a lighter note.

Thank you to every single subscriber who reads my articles. Thank you for caring about the trucking industry, for wanting it to be safer and better for everyone who depends on it (which is all of us). A special, extra-big thank you to my paid subscribers. Your support makes this work possible, and it means the world to me.

I wish you a very Merry Christmas. May your Christmas season overflow with love, laughter, joy, and precious moments with the people you love most.

Here’s to a brighter, safer 2026.

🩷

Exceptional breakdown of how a 1937 safety standard got misframed as Trump-era xenophobia. The California data is particualrly damning: 1,005 CA-domiciled trucks placed out of service in other states for ELP violations while CA itself issued just one. Thats not progressive enforcement, thats offloading risk onto everyone else's highways. The correlation between high ELP violation counts and elevated driver OOS rates, poor vehicle maintenance, and crash involvement completely undercuts the "this is just discrimination" narrative. When those two fatal crash examples are laid out, the emergency response communication breakdown isnt theoretical anymore, it becomes measurable in lost time and preventable deaths.